1.

It’s more important than ever to listen to Isis—to blast Isis from car speakers and home stereos, to close your eyes and rock your head to Isis, to play Isis for your friends and children and your friends’ children. The post-metal hardcore band Isis is an antidote (though not the exclusive one, or the peremptory one) to the pain we are experiencing as a species in the wake of patriarchal militancy—a reprieve from the spiritual sickness we face as a result of our persistent and violent estrangement from the feminine divine.

Because sure, heavy rock is your classic counter-cultural weapon, metal being especially useful in combat against religious extremism. But it is also important to re-establish certain semantic linkages in our brain that we have, through either deliberate tampering or sheer clumsiness, compromised. Isis, just like dozens of bands and songs and publications and geographical locations and superheroes, is named after a goddess. Yet the Isis-identified entity enjoying currency in the American news media is a rogue government/empire/terrorist organization that has nothing to do with the Egyptian deity—though their actions and ideologies do perhaps constitute a reactionary subconscious expression of a repressed urge toward goddess worship. Consider:

2.

Al-Dawlah al-Islāmīyah is the Arabic name for the Islamic state, unrecognized by the West, that currently controls portions of Syria and Iraq. As their goal is to re-establish an Islamic hegemony over all of Arabia and North Africa, they would prefer to be called The Caliphate. And though they have been known by various acronyms corresponding to their various incarnations over the past decade, the American news media—at least as of this writing—persist in calling them ISIS: that is, the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria—an epithet either calculated or subconsciously contrived on the part of the Western informational infrastructure to mock the group: by affiliating them phonemically with a pagan deity—and a female one, at that—the West simultaneously undermines the state’s religious zeal and annoys them, a finger in each eye of the enemy.

Not that Islam, or even an Islamic state, is the enemy. We go to great lengths as a professed liberal democracy to relegate our ire for other cultures and their regimes to the realm of the political: theology is not the crime but instead tyranny, or civil insecurity, or a lack of universal human rights. While this sort of PC rationalizing is classically obnoxious, the neo-theocratic policies of ISIS—at least as witnessed through several interpretive lenses, as is the case for me and most American citizens—are by all accounts repressive. Among various misanthropies, ISIS is renown for its violence against women, both physical and psychic. There are reports of Syrian women being stoned to death in public, of Yazidi women in Iraq being sold into slavery. The regime has imposed dress codes on women in controlled areas, and in a recent social media PR stunt, the regime’s female domestic rank-and-file (or at least bloggers purporting to be such) have advanced the claim that as they are not equal to men, and as their life-purpose derives from birthing future soldiers, Western women should flock to the men of ISIS.

Though this sort of violence is undeniably demographic—almost the exclusive sphere of young men from patriarchal social structures—it is not endemic to Islam or any other creed. Male-centric cultures have had hangups about women for as long as we’ve had a history to record it; for millennia, Roman pagans have been persecuting female Christians (their martyr-stories reminiscent of rape fantasies) and Hebrew lawgivers have been calling women unclean and proscribing their chastisement and Hindu priests have been throwing girls onto funeral fires and the popes have been calling Mary Magdalene a whore and puritans have been burning witches in the greater Boston area and Muslim extremists (and American mass murderers) have been shooting women on the street for the way they dress or behave and in general we humans have been doing a whole lot to convince ourselves (unsuccessfully) that the unavoidable feminine aspects of our special self-conception are, if not utterly meaningless and expendable, offensive.

What exactly have we been trying to avoid? Whose sanctity do we allege to protect while simultaneously immolating her body? Where is our mother, and why are we so afraid to call her?

3.

Isis—the woman also known as Iset or Aset, and popularly conflated with Ishtar, Annana, Astarte, or really any mother goddess, including the Christian Madonna—was born in prehistoric Egypt. Her name means Throne. Written history bears witness to her reign as the chief female deity of the Egyptians and continuing cult status in the Hellenized West well into the Christian era. She is the sister and wife of Osiris and the mother of Horus, both powerful projections of the male divine, but as the queen of popular cultic imagination in perpetuity, Isis has clout like almost no other god.

That’s why the male-dominant power structure fears her: she’s the even stronger woman behind the strong man. Osiris is killed by their jealous brother, Set—either cut into pieces or trapped in a casket. In some versions, he is drowned in the Nile. Isis travels around collecting all the pieces—in Plutarch’s version, she finds all the pieces except for his penis—and puts him back together again. She brings Osiris back to life long enough to conceived a son, Horus, who will contend with Set for eighty years for the office of his father. Like the biblical Jacob and the Olympian Zeus, he is aided by his mother, Isis, who tricks and thwarts and humiliates Set on her son’s behalf before the gods. (Horus, for his part, repays her by cutting off her head.) In the end, Horus becomes some sort of boss-god, a Christ figure whose eye can be found everywhere in Egyptian art. In some versions, Isis becomes his consort.

The men don’t seem to trust Isis. Even the gods, on Set’s advice, bar her from their meetings. But her spiritual value to the popular Egyptian mind is inestimable. Her magical powers to heal and succor satisfy a basic human need for mother-love. Even her own misery is our boon: the tears she sheds for Osiris nourish the flooding Nile delta. The people loved Isis, and her worship spread from Egypt to the Greco-Roman world, but the orthodox reforms of successive Roman Christian emperors effected its suppression, and Isis was relegated to the symbolic or subconscious or even demonic realm. But as the predominance of references to Isis in our modern world demonstrate, we keep drifting toward her—sometimes in spite of shame—as if trying to re-establish a historical fact about ourselves.

4.

One of my great scribal fears is that the music scene I fell in love with during my late adolescence will fail (due to the lack of any historical marker, like Woodstock or the Bronx River Projects) to garner sufficient documentary attention. I think this anxiety is common to many fans of live, quasi-underground music. People who are not gods and kings seem to coalesce out of ethereal anonymity as bands and crews and then proceed to work miracles on whole crowds before dissolving back into the populace, their legacy blown down the memory hole, their names abandoned, now open signifiers waiting to be re-appropriated. That’s what has already happened to many of Boston’s great millennial hardcore bands.

In the simplest sense, it was punk-metal fusion—you can obviously quibble over the genre ad nauseam—but it had an edge of zealotry (either lifestyle or aesthetic) that was maybe a literal echo of Massachusetts’s historical Puritanism, maybe not. Art had something to do with it. So did straight-edge, or correlative purist agendas. The best albums of the scene share this ethos: Cave-In’s Until Your Heart Stops and any of the first few Converge records. What they also share, along with Piebald and Agoraphobic Nosebleed and of course Isis, is an affiliation with Hydra Head Records.

Aaron Turner’s mail-order record distro—the prototype of Hydra Head—was born in New Mexico, but Turner was born in Springfield, MA. In the mid-nineties he went to the Museum School in Boston, and Hydra Head started pressing records for local bands. All the popular rock stations were playing alternative. Chuck Palahniuk was writing Fight Club, but the movie hadn’t yet spawned a thousand underground imitations. In an onomatological shift that would soon become overwhelmingly recognizable, Boston Gardens had been replaced by the Fleet Center. This is the cradle from which Isis, the band Aaron Turner fronted until 2010, was born.

The first time I saw Isis was at the Middle East, downstairs, in 2000. They’d just put out their first full-length album, Celestial, on Hydra Head. The show was opened by Candiria and headlined by Dillinger Escape Plan, both blistering, up-tempo, mathy bands. The Isis set, while grounded in the aesthetics of the scene, was hypnotically slow by comparison. The music crashed in devastating waves, patient and relentless. I don’t think it’s accurate to say that all five members were bald at the time, but I have this synthetic memory of five round white heads going up and down, bathed in blue and then orange light, over and over again while they strummed like warhorses in slow motion through the minimalist “Collapse and Crush.” It was monkish, devotional music. You couldn’t slam dance to it, even though it brought your heart up into your throat. It would have been best to fall writhing onto the floor to it. Or fall screaming through space.

This is music as religion—and not the narrow orthodoxy of form, but the spreading tree of cosmic spiritualism. Isis stand out in their rock pantheon as mystics. Their rhythms belong to the widest range of feeling. In this sense, they are saviors: they have redeemed us from the chauvinism of what heavy music can or should be.

5.

Hardcore has always been hyper-masculine. At its worst, it’s straight up anti-girl. In the documentary film American Hardcore, former Black Flag bassist Kira Roessler asks the question: “What am I doing here if you guys hate women?” In the time and place of my most extensive exposure to the hardcore scene (Boston, around the turn of the millennium), beards were very popular. Slam pits, the iconic arena of physical male bonding, engulfed floors. Giant men from local street crews did security. There were girls, but they were under-represented.

Many of the essential Boston/Hydra Head records of the period—their lyrics, their imagery, their mood—hover in post-adolescent ambiguity with regard to female sexuality. Some are more flagrant. In the women of the Converge mythos for example, we observe guilt, failure, malice. Revenge seems apt: the gorgeous artwork of The Poacher Diaries portrays a pixie captured by a fist and wrist-bound; and in the way-over-the-top poster art inside, naked women are depicted in the psycho-billy tradition with horns and tails, sexy vampires, killers. On face value, some of this stuff is (in addition to being silly) just plain misogynistic. On a deeper level, the neurotic obsession with femininity as a powerful other betrays an uncomfortable veneration—a musical worship of the goddess of death, to whom the all-male band members dedicate their selves and sacrifice their musical offspring.

Goddesses are not always nice. Neither is your mother. Anyone who brings you into this world promises you at least a modicum of suffering and certain eventual death. And while Isis puts Osiris back together, other goddesses take people apart. Kali wears skulls and skins, sucks blood, treads upon the dead. Diana turns Actaeon into a stag who is torn apart by his own hunting dogs. Lilith kills babies. Folklore is full of witches, hags, and beldams who want to hurt people, especially children.

It is this goddess—Man’s Ruin—whom we encounter in rock, even early blues. She’s a voodoo lady, well beyond the control of heroes and demigods, never mind young men just old enough to grow beards. Not only is her wrath terrible, but her independence from and even superiority to men is emasculating. You’re probably not going to fuck her, and even if you could she would dominate you. The traditional manner with which phallocentric societies have dealt with this goddess-anxiety has been vicarious: to violate corporeal women; to hurt and subdue them, sometimes in the name of their own protection, sometimes in openly expressed vengeance.

We find ghastly examples of this male crisis of identity and sexual impoverishment—literally innumerable throughout history, but here are two lucid citations from contemporary America: Charles Whitman stabbed his mother and his wife in their hearts before his 1966 shooting spree from the tower at the University of Texas, Austin. His own notes indicate that he did this for their benefit—sending them to heaven so they wouldn’t have to face the embarrassment of what he was about to do. And Elliot Rodger, in the 2014 video manifesto that preceded his mass murder, says, “Ever since I’ve hit puberty, I’ve been forced to endure an existence of loneliness, rejection, and unfulfilled desires, all because girls have never been attracted to me.” He promises to punish “you girls,” to whom the rant is ostensibly directed—to enter “the hottest sorority house at UCSB and … slaughter every single spoiled, stuck-up, blonde slut I see.” With typical zeal, he proclaims his assault “the day of retribution.”

That ISIS has used rape and the kidnapping and enslavement of women as weapons of war is not surprising, and it is not the result of a specific sectarian fervor; it is a reiteration of a war on womanhood. Male desires for women—either that they be sheltered or that they render sex—hang on the notion that they are the creation of men, ideas fixed in the male imagination and subject to revision as whim dictates. Women must conform to patriarchal standards or be discarded as faulty. They must not explode the borders or transgress a safe circumference of influence or ability.

The biological nature of women—mammary, maternal, multi-orgasmic—is forbidden the male. A guy feeling weak in its shadow has limited options for self-affirmation: the quick and dirty path of violence against women, or the arduous spiritual pursuit of synthesis. Wisdom. Dedication. That is to say: entry into and supplication at the temple of Isis.

6.

I have always thought of Isis’ music as being a rock equivalent of the extended male orgasm. Most rock music is designed to get you off, fast and cheap. Pop songs are sweet, but they rub the nerve raw, and once you’ve had a few, you’ve had them all. Isis, at their finest, brood on sensation. Their climaxes come in waves, after extensive romantic foreplay. And when they peak, they’re ecstatic: Turner leaps up an octave, Harris goes for the crashes, the guitars converge into choral unity—and unlike the other torchbearers of the genre, the band never falls for a few raging seconds into that chaos of cracked vocals or a misplaced kick or a wrong note. Isis never loses control; it is you, the listener, who lose control and fall through space amazed.

This is all to say: Isis is an all-male band, but their music is archetypally feminine-divine. It’s the expression of male devotees to the cult of Isis. There is a tragic endlessness to male goddess-devotion: the admission that as men we will never bear children, enjoy multiple orgasms, or have a complete 23rd chromosome. Still the cult persists in its veneration, either through supplication of the mother goddess or obsession over the witch queen.

7.

Isis goes into god mode with the release of their second full-length, Oceanic (Ipecac Records, 2002). You can’t fuck with this record. It’s the thickest, deepest, richest guitar chording available, and no wave crests until the sweet ache is almost unbearable.

I can’t say I ever understood the lyrics, not to Oceanic and not to any Isis album. Turner sings and chants and often screams the words so tonally that they leap out of semantic place into the realm of felt sensation. I always had the intuitive sense when listening to Oceanic that the track list constitutes a sea journey: We start on the solid and relatively predictable ground of “The Beginning and the End” and proceed through the tidal breakers of “The Other” and “False Light,” and by the middle of the album we’re out to sea—maybe under it—in a maritime dreamspace of bubbly arpeggios and weird radio-signal noises. Then the drums from “Weight” are heard a thousand nautical miles away and approaching inch by terrible inch and the song builds wave upon wave until we are in the midst of a maelstrom—and through the crashing sound and light, the voices of two women, Ayl Noar and Maria Christopher, reach us like the distant sound of birds or sirens. And then by “From Sinking,” we’re pulling into harbor on the other side of the world, safe but spiritually enriched.

It took Aaron Turner’s own exegesis to clarify the album’s surprising and compelling narrative. While I was right about the water, I was wrong about the journey. In an illuminating interview with Combat Music Radio from 2005, Turner lays the concept bare: Oceanic’s lyrics tell the story of a lonely man who learned to love a woman; but when he learned that his lover had been in an incestuous relationship with her brother, he goes mad and drowns himself. My current impression is that the whole album is happening in the protagonist’s mind, in the moments (minutes, seconds, microseconds?) before, during, and upon drowning: a reflection on love—a reflection of a woman’s love—that is simultaneously morbid and romantic, profane and divine, imbued not only with shame but with wistfulness. A tragedy overspread by the wings of the female divine, sister lover, mother destroyer.

The parallels to the Isis/Osiris myth are impossible to ignore: incest, drowning, death and rebirth. Was it coincidental, or was Turner always planning an invocation of the myth? And if so, why did it take seven years for a band named Isis to manifest such a deliberate reinvention?

We’ll never know; by now the band has broken up, the mp3 of the seminal interview is missing in action (at least all the links I could find were broken), and these days if you google “Isis” all you get is the jihadist army: young men smiling out of thin beards from atop assault tanks rolling into Mosul flying black flags.

8.

Isis is just two syllables. The fact that a mere couple of phonemes can contain such a broad range of human reality is one of the everyday miracles of linguistics, and a hallmark of the names of the divine. She is the mother of god and sustainer of men; the fact that we have not forgotten her is inscribed in our continual return to her name. It is a sacred name. One that should not be used lightly.

There is a legend that she tricked Ra, the sun god, into disclosing his secret name to her. She used this sacred knowledge to bind him to an oath: give to Horus, her son—whose eyes were torn out by Set—the sun and the moon. So that her son might see.

9.

Maybe ISIS’s weird marriage proposal will work and Western women will flock to the Levant to raise future jihadis. Maybe they’ll raise, instead, scholars and doctors and poets. Maybe they’ll raise girls, and the aging men of the first generation of ISIS will learn something about love. There are of course worse possible scenarios. But really, how long can anyone in a movement people are calling Isis continue to ignore these ideas.

Isis the band put out three more great albums after Oceanic, with suggestive evocations of the Isis myth scattered among Turner’s typically mystical lyrics. Turner married Faith Coloccia in 2009, and Isis disbanded the next year. In their musical incarnation, Mamiffer, Turner and Coloccia make the thick, elemental art-metal one might expect from a unified Tao. It’s a happy ending, except for the pissed-off young male fans who wish Turner was still screaming in Isis—but these guys will grow up soon, and maybe all boys get over their anxiety about girls (at least the ones who don’t kill themselves first, after killing as many women as they can).

And Isis, the goddess? The Wiccans and spiritualists keep her line open, but really you don’t have to go too deep to find her. Everyone—no matter how violent or misogynistic or dogmatic—has a mother. She’s in there, so she’s out here. You can try to ignore her, but it won’t work. You might as well call your mother. It’s been a while.

10.

I ascend upon the thighs of Isis.

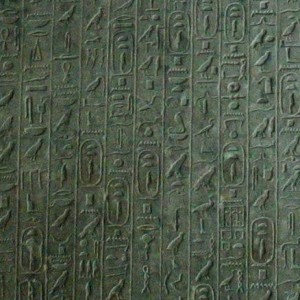

-from Utterance 269 of the Pyramid Texts; Saqqara, Egypt; circa 2300 BCE

Her form transformed from ash to golden throne.

-from Isis’s “Holy Tears”

_________________________________

Summer, 2014

Image: detail from Saquara Pyramid Texts

Regarding references: Each tidbit of contemporary news/history presented in this piece, while initially broken by a specific news outlet, has since become common knowledge. I have used (to the best of my knowledge) R.O. Faulkner’s 1969 translation of Utterance 269.