1.

The idea that Hamlet is trapped in a play is not new; Hamlet’s cage is sometimes thought to be the genre—the fact that he’s a poet and a philosopher trapped in a Marlovian revenge play. Harold Bloom has noted that Hamlet is in “the wrong play,” and Graham Bradshaw has gone so far as to identify an audience perception that Hamlet is a real man “trapped in a play and forced to perform.” This may account for the frequent observation that Hamlet seems to understand acting more acutely than even the play’s alleged actors—that the play is the epitome of Shakespeare’s veiled art criticism, his meta-theatrical commentary on the form and profession. Anyway, it’s a heady tragedy. The audience doesn’t get off on the passion and violence in the traditional cathartic manner. Instead, Hamlet takes us outside the form and into the larger realm of metaphysical speculation about the nature of being and the condition of human consciousness.

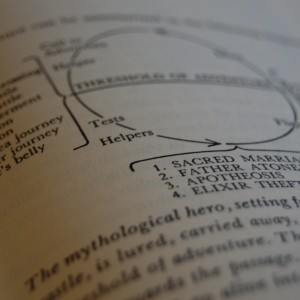

The last time I saw Hamlet, as performed by the Acting Company in 2014, I experienced what might be called an ontological catharsis. I’d been reading two books around that time—books that I should have read a long time ago: Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy and Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces. I’d even brought the slim Dover edition of Nietzsche’s book along to the show, to read before the lights went down and during intermission. These two texts synthesized with Hamlet, producing new and terrific realizations. It was as though I’d successfully paired foods or drugs. For the first time, I recognized Hamlet as a mythological expression of a specific existential anxiety: Hamlet’s problem—that he is an amnesiac trapped in a delusion of being—is our problem. And someone—either the prince or the ghost or the playwright or ourself—is telling us with explicit direness: get out of this play.

2.

Look, Hamlet’s trapped in Denmark. At Elsinore. His foil Laertes is given leave to go to Paris and play his role as gentleman scholar abroad, but Hamlet is told that his own return to Wittenberg is “most retrograde to our [Claudius’s] desire.” He is being detained by this evil king, who is both usurper and castrative father-monster. This is the guy who killed his own brother and married his sister-in-law. As far as actors go, he’s terrible; he plays the role of king weakly, and his kingdom is on the brink of invasion. Hamlet at various times compares Claudius unfavorably with his own father, the raw archetype, of which this beast-tyrant is an absurd shadow-puppet. And this worm of a man, he tells/commands Hamlet to stay in Elsinore, amid the filth and humiliation—to “be as ourself in Denmark.”

Claudius’s use of the royal plural is no mere affectation: he speaks for all the players. They’re all mean shadows, base simulations, totally unaware of their own artifice. If they stand for something or know something outside the script, they willingly reject it (Ophelia: “I know nothing”; Gertrude: “Speak to me no more!”). All of these characters actively pursue ignorance; they are content with a mediocre performance and a surface-reading of their lines. They accept the conceit of Claudius’s reign and marriage, Polonius’ doltish counsel, the fantasy that their kingdom is not on the brink of dissolution. And Hamlet is told to be like this. Forget Wittenberg (whatever that is). Forget the world beyond the stage. Stay here and be as ourself.

Enter Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. These guys are prop actors, and their arrival drives the artifice home. As Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead further demonstrates, they don’t really have to know anything. They don’t have to have separate identities or even a mutual one. They have no past—we have no reason to believe the pretense that they were some of Hamlet’s best buds back in the day, or even that they know where they are now—and they have no future: they will act as surrogates in Hamlet’s scripted death the way understudies might sub out an actor. (Hamlet actually says, of the subverted plot to kill him, “they had begun the play.”) Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are the most obvious indications that Hamlet’s life is a mock-up. Like the soon-to-arrive players, they are foisted upon him by Claudius with the express command to divert him, part of an elaborate contrivance (more elaborate than even Claudius knows) to keep Hamlet distracted.

3.

Hamlet is sometimes called “the hesitant prince.” But in the ninth chapter of Ulysses, James Joyce has a laugh at a provincial French translation of the title: Hamlet, ou Le Distrait (literally: The Distracted Person). This is closer to the tragedy’s terrible core: a distinct message is being delivered to the hero, but there is too much interference. Hamlet gets glimpses, but there’s always some villain hiding behind an arras, some girl rushing into the room to remind him of something; even if he can ignore or defy the more obvious ruses—Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s transparent attempts to distract him, the players and their plays, everything Polonius does and says—there is a dead father, a ghost with the name of Hamlet, looming above and below, reminding him of the necessity of revenge. His distraction is fatal.

In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell relates the story of how Gautama, the future Buddha, raised among the Brahmin caste as a young prince, was shielded by his kingly father for decades from any glimpse of natural truth. He was fortified against any inkling of suffering and death. Forty-thousand dancing girls were charged with entertaining the boy. He had servants and toys and games (gibes and gambols) shoved constantly into his immediate sphere. He was kept distracted. But signs of the meanness of nature intruded. He caught a glimpse of a dying man by the castle gates. He saw a beggar, a cripple. The more the king scrambled to distract the boy, the more abundant the omens. And then, one day, he saw a meditating holy man, free of desire and pain, and thus was born the mission of enlightenment.

Hamlet is littered with such auspices of ultimate reality: indications that what he sees is a shadow-play. The most explicit of these is the apparition of his father’s ghost. Though others have seen the ghost, it will not speak to them. Hamlet, as tragic hero, must confront his father’s ghost, speak with the specter, receive his supernatural instructions, and be sworn to revenge.

He’s supposed to kill Claudius. So he thinks. That this is all metaphor—that the true mission is to slay the old self and transcend, to escape the role and the play—is not inherently obvious to Hamlet. After all, he is in a revenge tragedy. The stage and script are his chief distractions, the impediments to his transcendence.

4.

Shakespeare was inclined to compare the stage to reality; the trope extends to several plays, maybe all. Hamlet is a thespian’s nightmare: you are in a play and you’re the only one who knows you’re in a play, and everyone else is acting a role and they won’t ever cut or remember what they should remember from the real/external/authentic world, and when you try to talk to them off-script they act as though you’re mad and you yourself begin to believe it. The only way out is your own scripted death. (And then, nightmarishly, you have to renew your role the very next night.)

That’s because the play—the cage, The Mousetrap—is conscious life, this mortal coil. The play is the dream-interlude between two periods of waking. The greatest mistake the actors have made—everyone, perhaps, except Hamlet (and maybe the ghost, who is also named Hamlet)—is believing that the contents of the play—the set, the sound, the script, and the banality of the personae that literally masquerade as real emotive beings—is the authentic universe. Hamlet is on the verge of a deeper realization, and is thus mad.

What might he realize? That the ego is an illusion. That there is only one mind, the mind-at-large, but the mind-at-large is fractured and afflicted with amnesia, lost in its own psychic adventures and fantasies; and that this play, Hamlet, which he is experiencing in the first-person with apparent felt sincerity, is in fact the neurotic labyrinth of the dis-integrated mind. Elsinore and Denmark and the play itself stand for the veil of maya, beyond which lies the infinite oneness of reality.

That’s the essence of “to be or not to be.” It is the fundamental question of the cosmic mind-at-large: If everything is one, and if each individual consciousness is part of (or, paradoxically, identical to) the mind-at-large, then why did we choose to become many? Why the differentiation of the ego? Why the big bang? If, as various astro- and quantum physicists have suggested, all matter has since the beginning of time been interacting and diversifying and restructuring with the cumulative effect of manifesting self-awareness, and if that self-awareness is realized in those of the universe’s higher intelligences of which Homo sapiens is one, and if this self-awareness leads us inexorably to the conclusion that all matter and energy comprises one universal mind and soul and body and will—the mind-at-large, the God will—then why did we ever choose to experience individuation or existence at all, if only to come around to the same conclusion, and to crave closure and release from this ridiculous goose-chase: being to non-being to being to non-being, or rather: samsara to nirvana to samsara to nirvana, or rather: theater to reality to theater to reality. Why this adventure of the ego? Why the wheel of rebirth? And when will it end?

Hamlet’s true goal is to break that cycle. For now, he is temporarily detained—he “lack[s] advancement” to the wider realm of existence. His dramatic condition—fatherless, detained, arrested, deprived of birthright—are an imitation of his larger spiritual condition. He craves union with the father, the archetypal Hamlet, the true extra-theatrical, original Hamlet (Shakespeare, or the mind-at-large). He is assigned to murder his uncle, who is the false version of his father and hence a false projection of himself: Claudius is what Hamlet may become if he stays, if he becomes king of Denmark himself. Claudius is a pretender. He is a tyrant. He is like the blind and ignorant demiurge of gnostic Christian cosmogony who thinks he is a creator or a director but in fact is a mere facet of an incomprehensible divine oversoul. Comparisons between him and King Hamlet are comparisons between a corpse and an astral-body. Claudius has succumbed to everything the protagonist must strive against: pride, degeneracy, debauchery, delusion. Claudius believes in the play baldly. He must be sacrificed in order to open our eyes to the true nature of things.

To kill Claudius will be suicide for Hamlet. Any murder is suicide, when one considers that we are all expressions of the mind-at-large. But it will be the murder of the grotesque world of semblances, of the too-heavy flesh, of the carcasses that will show up all over this play. The murder of Claudius will set Hamlet free (i.e. he will die—be released from the play).

Unfortunately in this he follows script: and he collaterally kills a whole bunch of other people and himself. Now he’ll have to return the very next night and, in a state of pretended amnesia, re-enact the whole bloody saga again as if he didn’t know it was a farce.

5.

Hamlet knows he will die. It is the reason he cannot love Ophelia anymore. Ophelia is deep in the labyrinth of delusion. When Polonius dies she goes mad, unable to countenance death. She cries that her father “never will come again” (even in a play where dead men return, in a universe where death merely means reconfiguration). By her own estimation she knows “what we are, but know not what we may be.” When she drowns, she does so with the impression that she is not drowning. She is in a fantasy world, looking at the reflection of nature in the mirror-surface of the water, “incapable of her own distress.”

To impregnate Ophelia is equally terrifying. Not only does this ensure another son without a father, but it ensures another iteration of Hamlet, another genetic prisoner to the eponymous play, another life lived outside the pleroma. Another adventure, revenge, tragedy. Over and over, Hamlet and everyone else gags on the morbid fact of life: unless they’re glossing it over for the purpose of psychic repression, everyone is overmastered by the weight of the surety of death. Hamlet has reason to believe that in death there will be release—he is given the key to his own enlightenment, the dagger with which to slay his shadow self—but Ophelia shows no faith in existence beyond Elsinore. To wed her is stagnation, and to lead her on is just cruel.

Hamlet, in his “antic disposition,” taunts Polonius with a folk superstition: “If the sun breed maggots in a dead dog, being a good kissing carrion … let her [Ophelia, his daughter] not walk i’ the sun. Conception is a blessing, but as your daughter may conceive—friend, look to’t.” On the idiot level, this is mad rambling (though there be a method in it); on the plainest level of comprehension, this is a dirty joke about the old man’s daughter; on a mythological level, Hamlet has linked the dead body (carrion) to the living flesh capable of reproduction (Ophelia)—linked sunlight to semen and maggots to babies and correlated death and birth quite economically.[1]

Life-and-death, the simultaneity of both, is the overriding theme. All illusive opposites are wed. Funeral meats furnish the immediate wedding. Marriage is depravity. Jesters become skulls, friends are strangers; player kings weep at art that merely seems, while the actual king merely poses and feigns. All joys tend toward tragedy, and all living things die.

We get recursive death-imagery throughout. The Player King poses as Pyrrus posing above Priam as the god of death, sword arm raised above him (a god to whom Priam, in this retelling, submits almost willingly). In the Acting Company’s production, Hamlet strikes this same pose above Claudius—when Hamlet chooses not to kill his praying uncle unsullied—and waits, thinking, reconsidering. Being distracted. And they close with the entrance of Fortinbras; they cut the last fifty-or-so lines and killed the lights right after Fortinbras, armed from head to toe and carrying a sword, steps through the stage curtain and stands shining above the other characters, who mostly lie dead in the foreground. This play, under this production, ends with the entrance of the god of death. Which is a nice ending to a revenge play, even if it is too late for Hamlet to defy augury, reject the role, and walk off stage (which is the only ending that matters).

6.

In 1989, Daniel Day Lewis walked off a London stage mid-performance. He had been playing Hamlet, in a staging by the National Theatre. This is of course legendary, and the dominant narrative is that he saw the ghost of his own dead father. No shit: Daniel Day Lewis is a method actor. He was Hamlet, and Hamlet most certainly sees the ghost of his dead father. But why did Lewis refuse to return to the stage? Why did he not let the episode pass and then resume this prestigious role?

Because he got the message. Because he recognized that between every line of the play, Shakespeare was shouting at him, YOU NEED TO GET OUT OF THIS PLAY NOW, OR YOU WILL BE TRAPPED HERE FOREVER.

Hamlet is a perceptive character. Harold Bloom calls him “too immense a consciousness for Hamlet.” In addition to the prince’s raw talent—the intellectual ability to conceive of his ontological dilemma—he has as evidence of the conspiracy against him one of the play’s most celebrated motifs: the power of dramatic art and similitude.

Over and over, Hamlet is reminded that his life is not only temporary and trivial, but literally a play. From the very beginning, he laments that his clothing, looks, and even vocalizations merely seem whereas he feels and is. There’s an overriding anxiety that the world will reveal itself (or has revealed itself) as a “dumb show.” The arrival of the players—and shortly thereafter, the staging of The Murder of Gonzago—is the motif’s climax; it’s an omen to all the cast and audience: YOU ARE IN A PLAY. They watch, rapt, all on the verge of recognition. This little skit is uncanny and unsettling on an ontological level, but they can’t make the full leap. That’s up to us.

Look closely: The players, as they’re called, are always a bit lower-fi than their counterparts: their costumes are burlesque, and their makeup painted “an inch-thick” so they look spectral, Japanese or Greek elements in an Elizabethan play. Hamlet calls them the “abstract of the time.” Polonius marvels that the Player King, while recounting Pyrrus’ slaying of Priam, can force a tear as though artifice were reality (even Hamlet, loath to condescend to Polonius’s naiveté, repeats this later, amazed). Only Hamlet—and perhaps we, the audience—is given to understand the implications of this mis en abyme: we are all deluded or pretending, actors, caught up a little too much in what is essentially make-believe.

Hold the mirror up to nature, Hamlet tells the players. But what sort of reflection will we get? Will we see the pancake makeup, the motley? Will we see the wires and the trap doors? Certainly Hamlet does. That’s why he’s mad. No, he’s ecstatic. He’s “blasted with ecstasy.” He is literally ex stasis, at a meta-theatrical remove unavailable to the other characters.

Someone is trying to show him, and us, how absurd the whole pantomime is; how our flesh is too heavy, our dispositions antic-seeming, our bodies nothing but the quintessence of dust. Confronted with a play within their own, even the dullest characters feel unsettled by the platitude. A good cast will give you that during The Murder of Gonzago: shocked recognition, repulsion, anxiety. When you watch the characters watch the players, you are watching an audience react to theater.

7.

Ancient Greek tragedy had a chorus. The appearance and role of the chorus changed over time, but basically it consisted of a spectral group of masked performers whose hymnal lines echoed or reacted to the sentiments of the tragic hero. Sometimes they realized things before the hero. They were like a proxy audience—they may have actually been the audience at the dawn of the art, when it was indistinguishable from religious rite—and their words and behavior were cues to the public, like the conceit of narration in fiction or a voice-over in film (or, even more accurately, like the soundtrack of a film). It is the chorus that experiences catharsis and transmutes the ineffable pain into song—that essentially emotive medium—in order to fully move the audience.

Over the course of the classical period of Greek tragedy, the prevalence of the chorus declined, a transformation Nietzsche lamented. By Shakespeare’s time, we are left with a single guy on stage, prefacing Henry V or Romeo and Juliet with his hat in his hand, more of an apologist than a psychopomp. A cynical sort of realism had diluted the theatre: we could, by the Elizabethan age, agree to the illusion—concede that Hamlet’s troubles were not real, that his plight was not ours, and that we could all leave the theater and return to the mundane. In exchange, we give the play our faith. We believe it to be a representation. We suspend our critical faculties and become passive onlookers. It takes an act of overt deconstruction to rouse us, as from a dream, to the reality of artifice.

The asides and soliloquies that typify Shakespeare’s plays are always fourth-wall breakers. An extra-theatrical intelligence speaks directly to us, the so-called “real” audience, using as its mouthpiece characters who often don’t understand the depth of their own language. These are vestiges of the chorus, probably harkening back to that pre-classical time when the line between stage and audience was non-existent and we all participated to varying extents in the dramatic dithyrambs of which our present theater is the descendent. Dada, Brechtian theater, Absurdism, and contemporary metafiction seem to me to be attempts to bring theater and representational art in general back into the Dionysian sphere; to remind us that though this is very obviously fake, it is also very obviously real, and though this is ostensibly a revenge tragedy, it is also (like all art) an encoded message, a story within a story.

The secret story here—the underlying plot of Hamlet, once you strip away the semblance of funerals and marriages and betrayal and revenge—is a rendition of the monomyth (a term I got from Joseph Campbell, who got it from James Joyce): the singular, all-encompassing narrative of cosmic consciousness. All of nature’s voices are an expression of the monomyth: birds sing, bees dance, molecules crystallize into geological structures. People tell stories. Rather, the story: Once upon a time there was a being who went on an adventure—into the forest, into town, into the belly of the beast, into the role of Hamlet, into an egocentric state of awareness—and learned something and then returned to the original state. Jesus does this. So does Odysseus. So does every so-called soul in its transit from birth to death. This is the only story in this universe. It has a lot of variations, but ultimately it’s the story of an adventurous and terminally lonely mind repeatedly understanding and forgetting itself through infinite iterations of expansion and regenesis.

It’s the story of the physics of the universe. It’s the story of the one true God and the pantheon of the gods. It’s a story written on a lemniscate that ends at the starting point.[2] It’s a tragedy.

8.

There is a tradition that William Shakespeare played the ghost. He should have been double-cast as the Player King. All kings in this play are The Player King. Claudius is just acting like a king, and badly. And even Hamlet’s father is a player king; because (boing!) everyone in Hamlet is a player; Hamlet is a play. If you can believe that—that a bunch of characters in a play sit down to watch a bunch of characters in a play pretend to be them—then you can accept the recursive proposition that we too are being watched; that we too seem like gaudy mummers, gross caricatures in the eyes of some audience we cannot perceive beyond the lights of this very bright stage.

Watching us watch Hamlet, the audience feels an occasional pang of some essential, unnameable sorrow; and they congratulate themselves that unlike us, they are not trapped, scripted, fated for death. Then they walk out of the theater and into the sunlight of their own closed set.

_________________________________

Summer, 2014

Notes:

1^ Joseph Campbell, too, gives us the virgin-impregnated-by-the-sun myth in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, but he cites it to American Indian mythology.

2^ See John Barth’s “Frame Tale,” which is designed to be cut out and taped together to form a continuous narrative (Lost in the Funhouse. NY: Doubleday, 1968).

Image: Detail from The Hero with a Thousand Faces (245).

References:

Bloom, Harold. Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. NY: Riverhead/Penguin Putnam, 1998.

Bradshaw, Graham. Shakespeare’s Skepticism. NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1987.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. NY: Bollingen Series XVII/Princeton University Press, 1949.

Joyce, James. Ulysses. c. 1922 (Take your pick of editions.)

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Birth of Tragedy. 1872. (Ditto.)

Stoppard, Tom. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead. 1966. (Ditto.)

RETURN TO THE MAIN PAGE